As pressure grows to whitewash history, historical markers grow more inclusive

Historical markers, once criticized for whitewashing history, increasingly are a defense against it.

Among my daughter's college visits in 2022 was Indiana University, which just so happened to be my alma mater. As I pointed out the spots of my youth, I was surprised as I approached People's Park, a spot near campus seared in my memory as a hangout spot for hacky-sackers, hippies and busking hammer-dulcimer players. I had never thought of how it got there.

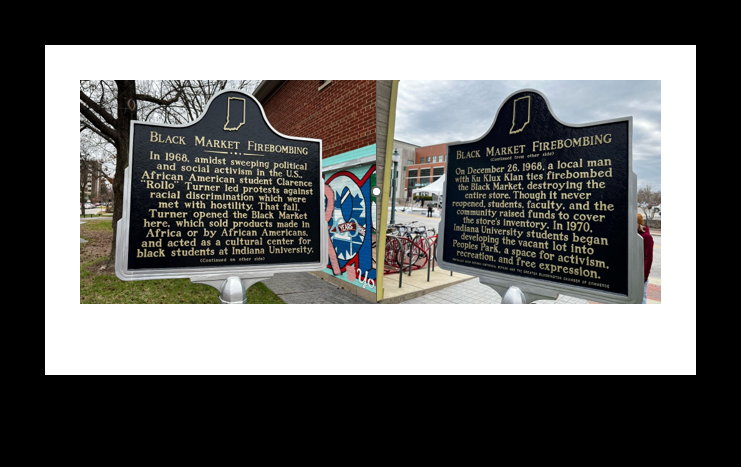

Until I came upon a historical marker posted in 2020 – shall we say, long after I graduated. It was titled, "Black Market Firebombing," and it read:

In 1968, amidst sweeping political and social activism in the U.S., African American student Clarence “Rollo” Turner led protests against racial discrimination which were met with hostility. That fall, Turner opened the Black Market here, which sold products made in Africa or by African Americans, and acted as a cultural center for black students at Indiana University.

On December 26, 1968, a local man with Ku Klux Klan ties firebombed the Black Market, destroying the entire store. Though it never reopened, students, faculty, and the community raised funds to cover the store’s inventory. In 1970, Indiana University students began developing the vacant lot into a People’s Park, a space for activism, recreation, and free expression.

A sign saying a little means a lot. A historical marker, as usual, can't cover all the pertinent details (the store didn't reopen because the building was beyond repair, the students who took over the space where white "Yippies", the KKK had a concerted campaign of intimidation in Bloomington during that time). But its mere existence, particularly in a highly trafficked area right off the Indiana University campus, covers a nominally small story that taps into a bigger narrative about racism in the United States, and the response to it.

With so many fights over how history is being taught in schools, with explicit efforts to put Great White Men and American Awesomeness at the center of discussion, efforts over the last decade or two (such as Virginia's Black history initiative, in which 63% of all markers posted since 2019 center on the topic) to center marginalized populations on historical markers threaten to make plaques a more critical and complete study of the American story. Put "historical marker" or "historic marker" in Google News are more often than not you'll find a dedication centered on a community traditionally ignored on plaques.

I'm not saying historical markers can, will or should substitute for a critical history education. But depending on where you live, you truly can do worse.